After our Walk of Shame to the Cosmiques hut following the abortion at the base of Mont Maudit, we ordered a bowl of soup and a panaché (lager and lemonade), and then I took a two-hour nap. I woke up for a cosmic dinner and then went right back upstairs for a blissful 10 hours in the rack. In the morning, I was a new man.Anything we could do on our final day in Chamonix would have to be short and close to the hut because we had to catch the last lift down in order to make it to our flights from Geneva the next morning. The night before, we’d had dinner with Kathy Cosley, an American guide who lives in Europe and was heading up Mont Blanc with a client. I was eager to get her opinion on what to do, in part because I'd already studied the website that her husband, the guide Mark Houston, had put together; this superb site is packed with detailed route descriptions and photos from many Alpine classics, and I highly recommend it to anyone planning a trip. Cosley recommended the Chèré Couloir on the Triangle du Tacul for a good quick route, and so, as the morning clouds lifted and a stiff wind buffeted the hut, that’s what we did.

The Triangle is the site for half a dozen “sport ice” routes, including several short but very beautiful goulottes (narrow couloirs). Although the climbing on some of these is difficult, and the approach and descent are threatened by serac fall and all the other dangers of Alpine routes, they’re “sport ice” because they’re so close to the hut and lift, and because you can just rap down whenever the going gets too tough or you run out of time. John and I climbed three long, excellent pitches of sticky, one-hit ice on the beautiful Chèré Couloir. We had planned to continue up the easier mixed ground to the top, but at the third belay, after all the steep ice, John suggested we might just have time for another route if we rapped now.

Specifically, we thought we might just have time to climb the Eperon des Cosmiques (Cosmiques Spur), a five-pitch rock climb that leads to the upper Cosmiques Arête, a classic easy mixed ridge which in turn regains the Aiguille du Midi summit, where we had to go anyway to ride back down to Chamonix. It would surely beat a snow slog. John, for whom the easy way is never sufficient, suggested a mixed "shortcut" along a ridge to return from the Chèré Couloir to the hut instead of the easy snow walk, and by the time we got there it was after noon.

The last lift down from the Aiguille de Midi was at 5:30. We could not afford to miss this lift and bivouac again. The rock climb was looking a bit dubious; perhaps we ought to just climb the more straightforward Cosmiques Arête and make sure we caught the lift.

“We've reached the age that we don’t have to do stupid things that we’ll regret later,” John said, ignoring the fact that we’d already done one stupid thing on this trip that we’d regret later. But when we walked down the hill from the hut, we hardly needed to speak to make the decision to walk over to the base of the bigger climb, the Eperon des Cosmiques. John quickly did the math: If we could clear the crux roof halfway up the climb by 3 p.m., that ought to give us enough time to finish the route and the ridge above and still make the lift. If we weren’t there by 3, we’d rap off and slog up the snow slopes to the lift station. The race was on.

Climbing granite in big boots while wearing a moderately heavy pack is never much fun, even if it’s relatively easy, well-protected granite like our route on the Eperon des Cosmiques. But, although we were huffing and puffing as we hurried up the steep jam cracks, John and I were having a blast: At last we were moving well and feeling somewhat competent. We quickly caught and passed a pair of climbers on another, easier route to our left.

With a quick yank on the sling conveniently dangling from the route’s big roof (5.10), we were past the crux. Two more pitches brought us to the snow at the top.

Here, we were about midway up the Cosmiques Arête. A huge line of climbers had started up the route earlier, and we could see many of them ahead of us on the finishing pitches. But, with our late and unorthodox approach, we found ourselves all alone on this crowded classic. In mid-September, the ridge wasn’t as pretty as it might have been when covered with more snow. But it was still great fun weaving around the huge gendarmes and climbing up and down steep little steps, one foot on rock, one on ice, in the classic style. Nearby we could see two climbers perched dramatically on the main south buttress of the Aiguille du Midi.

We moved together with a shortened rope between us, and soon we were at the base of the final step, where a short, fixed aid step off a giant bolt and a little chimney pitch gained the final moves: a steel ladder bolted to the tourist complex on the summit ledges of the Aiguille de Midi.

It felt good to have actually climbed something, no matter how trivial these climbs had been compared with our original goal. John, to his everlasting credit, was all smiles. I was psyched, too, but also a bit sad: My unexpected European vacation was over.

To read the first of these reports from the Alps, click here.

Monday, October 29, 2007

Chamonix: A Sweet Finale

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

6:24 PM

4

comments

![]()

![]()

Friday, October 19, 2007

Cursed in Chamonix

John Harlin and I had only three days to get something done in the mountains before we had to fly out of Geneva. We were overloaded with possibilities: back to Grindelwald for the Mittellegi Ridge on the Eiger or the beautiful Schreckhorn; to Zermatt or Zinal for a route on the Matterhorn or the Zinal Rothorn; or to Chamonix for…well, for a hundred different possibilities. In the end, the unmatched convenience of Chamonix climbing, combined with a free lift over to France with Jerry and Daron Robertson, tipped the balance in favor of Chamonix-Mont Blanc.I hadn’t been to Cham in 20 years, and the last time had been a learning experience. We were there in May, and the weather was iffy. More importantly, we didn’t have skis and we were too broke or cheap to rent them. I remember sleeping at a jam-packed Argentiere Hut, the first stop on the Haute Route, at the beginning of a holiday weekend, and out of at least a 150 people at the hut we were the only ones without skis.

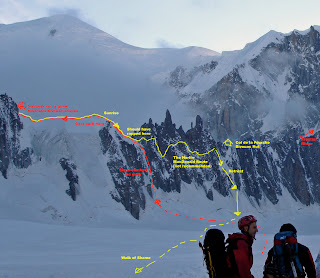

This time, the stars were lining up. The weather was perfect, and Roger Payne, who’d just been guiding on Mont Blanc, had told us conditions were excellent on the high-altitude mixed routes, which is just what we hoped to climb. We were aiming for the Frontier Ridge on Mont Maudit, a 14,648-foot satellite peak of Mont Blanc. The route was No. 50 in Gaston Rebuffat’s Le Massif du Mont Blanc: Les 100 Plus Belles Courses, which placed it right in the middle of the difficulty range for the massif, at least in 1973 when the book was published.It was midafternoon before we’d arrived in Chamonix, sorted a place to store our bags and computers, bought a bit of food and a fuel cartridge for John’s JetBoil, and made our way to the Aiguille du Midi tram. There was just one problem: When we’d called for reservations at the Refuge des Cosmiques, the hut where we planned to spend the night, we learned that it was full. Well, no matter, we thought: We’ll do the approach in the evening, stay at a bivouac hut right on the Frontier Ridge, and that way we’d do the beautiful three-hour walk across the glacier in daylight instead of the predawn blackness.

After riding the stupendous Aiguille du Midi lift, which gains about 9,000 vertical feet in two stages, we geared up, tiptoed down the frightening snow arête outside the Midi, and set off across the glacier. This was easy going, but it was a long ways, and it was after 7 p.m. when we neared the base of our ridge. We bumped into two Italian guys headed down, and John showed them the map and asked which ice gully led to the hut. Now’s probably the time to say there were actually two huts shown on our map, the Col de la Fourche bivouac hut and a second hut, a bit farther away from the start of the route but still on the ridge, called the Refuge Ghiglione. The Italians had something emphatic to say about one of these huts, but given the language barrier we couldn’t make out which—or what the issue was.

To reach the ridge, you have to climb about 400 feet of moderately steep alpine ice. As we neared the obvious ice slope leading to the Col de la Fourche, we saw at least six climbers above us at the col or finishing the ice. Having done no research on this bivy hut (stupid, stupid!), we weren’t sure how big it was or even whether it had bunks or blankets. Since we had neither pads nor bags, we definitely wanted blankets. So, we opted to shift course and climb a different ice gully to reach the Ghiglione hut.

It was pitch dark by the time we reached the hard-packed snow arête leading to the Ghiglione. John was leading and I was concentrating on moving precisely, since we were roped up but had no gear between us. John paused on top of a big cornice and yelled back, “This doesn’t look good!” No it didn’t. Turns out the Refuge Ghiglione had been removed in the mid-1990s because its foundation was eroding, but for some reason it was still on the maps. (The photo at right shows the hut's spectacular setting, cantilevered over the Brenva Glacier, sometime in the 1980s.) All that is left now is a steel platform. We were stuck and we began to prepare for a very cold mid-September night. Fortunately, we had a stove and bivy sacks, and even more fortunately the wind stayed calm overnight. John soon discovered that the big white mound beside the platform that we thought was snow was actually old fiberglass insulation, so we stripped off sheets of this and made fluffy mattresses to lie on—good for insulation, bad for the lungs. We knew we’d survive the night, but we also knew we were going to be miserable for the next 8 hours or so.

No it didn’t. Turns out the Refuge Ghiglione had been removed in the mid-1990s because its foundation was eroding, but for some reason it was still on the maps. (The photo at right shows the hut's spectacular setting, cantilevered over the Brenva Glacier, sometime in the 1980s.) All that is left now is a steel platform. We were stuck and we began to prepare for a very cold mid-September night. Fortunately, we had a stove and bivy sacks, and even more fortunately the wind stayed calm overnight. John soon discovered that the big white mound beside the platform that we thought was snow was actually old fiberglass insulation, so we stripped off sheets of this and made fluffy mattresses to lie on—good for insulation, bad for the lungs. We knew we’d survive the night, but we also knew we were going to be miserable for the next 8 hours or so. I sure admire people who can suffer through an unplanned bivy and then snap to it the next morning, climbing hard. I felt like crap in the morning—sleepless, dehydrated, and with a touch of altitude sickness—and once we got under way we quickly made another tactical blunder. We should have rappelled back down the ice we’d climbed the night before and then climbed back to the ridge to get en route. Instead, we tried to traverse along the side of the ridge, which required tedious, moderately difficult mixed climbing, plus a couple of lowers and rappels when we got off route. Had we actually climbed the Frontier Ridge of Mont Maudit, I’m certain we would have done the crux before we had even started the actual route. As it was, we never even made it to the Col de la Fourche. As a hot sun beat down upon us from a windless blue sky, I pulled the plug and we bailed. We rapped to the glacier and began the exhausting Walk of Shame to the Cosmiques Hut.

Mont Maudit, by the way, means "cursed mountain." Next up: Redemption! To read the first of these reports from the Alps, click here .

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

4:00 PM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, October 17, 2007

The Robbins Route

Our organized media tour in Switzerland had ended and the leashes were off: In other words, it was time to climb.

John Harlin wanted to return to the Tour d’Aï above Leysin, where he had lived for several years during the 1960s, and where his father had started the International School of Mountaineering. For a brief time, because of the senior Harlin's influence and his need for instructors at the new school, this tiny town was one of the most important centers of climbing in the Alps. In particular, it was the center of American influence, when Harlin, Tom Frost, Gary Hemming, Royal Robbins, and others brought Yosemite skills to the Alps and climbed major new routes like the south face of the Fou and the American Direct on the Drus—perhaps the only time when Americans made a significant mark on Alpine history.In 1964, John Harlin II climbed the first two pitches of a steep limestone route on the Tour d'Aï. Harlin veered off to the left below a final headwall. The following summer, Royal Robbins was running Harlin's climbing school and the two were working on the American Direct. Between forays to Chamonix, Robbins repeated the Harlin route on the Tour d'Aî and then forged straight up the overhanging headwall, using a few points of aid. A short time later, he returned with George Lowe and led the entire route all free at around 5.11b. In 1965, this may have been the hardest free pitch in the world, and Robbins must have done it with almost no pro in the first half of the lead. I'll bet only a handful of American climbers have ever even heard of this route, but it was a tour de force.

John Harlin III had made a date to meet up with Jerry Robertson, who was John Harlin II's partner during his first attempt on the Eiger in the early 1960s, and to climb the Harlin/Robbins route with Jerry’s son, Daron. I tagged along, and it was a fantastic experience.The first two pitches, which John’s dad had climbed, followed a corner and crack system up a vague pillar. We carried some pro, but we didn’t need much: The route had been fully retro-bolted some years earlier. These two pitches could have been protected without bolts, but the second would have required numerous large cams; Harlin's dad had used wooden blocks as “pro” for the wide crack. I wasn’t really sorry to see a good bolt every 10 feet or so.

Daron, a 5.13 climber from Tucson, was our rope gun for the Robbins pitch, and he quickly completed the long, overhanging lead. When I followed, I was blown away by what Robbins had accomplished in the mid-1960s. He would have found almost no protection in the first 30 or 40 feet; above that, although the route followed a series of cracks, the face was so steep that hanging on to place pitons (the only option at the time)

would have been absolutely desperate. Moreover, the climbing was hard. Sustained and fingery, the pitch climbed over two crux bulges, with a sting in the tail in the form of a deceptive pod in the final crack. I could not imagine leading this climb without the bolts. I was happy just to follow it cleanly.

Each of us enjoyed this climb in different ways. Though the climbing was technically easy for Daron, he hadn’t done a multipitch route since he started climbing 10 years earlier. For John, it was a trip down memory lane, and a chance to celebrate the accomplishments of his father. For me, it was a superb and eye-opening climb, my first in Switzerland, and I felt privileged to explore this little-known setting of climbing history. Most climbers are—or should be—familiar with Royal Robbins' ground-breaking climbs in Yosemite: He was the master of big-wall rock craft during the Valley's Golden Age. But our day on Le Tour d'Aï gave me a much greater sense of Robbins' incredible free-climbing prowess. Given modern shoes, protection, and training, what might he have accomplished today?

To go to the start of these reports from Switzerland, click here.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

9:12 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, October 09, 2007

The Tour d'Aï

After four days in Grindelwald, our little group of journalists drove over a high pass to the French-speaking side of Switzerland, specifically to the village of Leysin. This is where John Harlin III, star of the IMAX film The Alps, spent part of his youth in the 1960s. And what a place to be a kid! Skiing, hiking, climbing all in your back yard, with a view of the Mont Blanc massif shining across the valley of the Rhône. During the ’60s, Leysin was a great center of Alpine climbing, specifically the American and Anglo contingent—Dougal Haston, Royal Robbins, Gary Hemming, Tom Frost, and others—who based themselves here to work for the international school that John Harlin II cofounded and to hang out with friends and plot new routes.

We sampled a range of Leysin life, from mountain biking and hiking to eating, eating, and more eating. But the highlight was a via ferrata on the Tour d’Aï, a limestone fin that looms over the Leysin ski slopes. Via ferrata routes were invented in the eastern Alps during World War I, using steel cables, ladder rungs, and carved steps to safeguard the movement of troops through vertical terrain. Now they’re everywhere in the Alps, and some of them are like Jungle Gyms for adults, with crazy overhanging ladders and swinging bridges across otherwise unclimbable terrain. But the Tour d’Aï via ferrata followed a mostly natural line across ledges and up chimney systems; it required about 1,000 feet of traversing and climbing to ascend the 350-foot cliff.

Our guide was Julie-Ann Clyma, a charming Kiwi who lives in Leysin with her husband, Roger Payne, an Englishman and also a mountain guide. For many years, the two have done major expeditions to Asia and elsewhere (right now they’re attempting unclimbed peaks in Sikkim). Payne is like an Energizer Bunny with devilish tendencies. The night before, he had dragged one of our group to the Yeti bar in Leysin for karaoke, and the two men-children hadn’t made it home until after 3 a.m., making for a painful Alpine start for Payne, who was due to start guiding a Mont Blanc climb the next day.

After hiking up the ski slopes to a saddle below the cliffs, we kitted up. Most via ferrata climbers don’t use a rope or belays; instead, you attach a lanyard to your harness, equipped with two quick-locking carabiners and a clever shock-absorbing gizmo. As you move along the route, you always keep one carabiner clipped from your lanyard to a steel cable bolted to the wall. If you fell, the cable and bolts in the cliff would keep you from plunging too far, though you’d likely be battered. A few people in our group were nervous about the exposure, so Julie-Ann tied them in to a short rope, which she could pass through the open ends of the eyebolts holding the cable, providing quick simul-climbing anchors.

I’d done a few portions of via ferrata routes in the Dolomites, just poking round on rest days. But this was the first full route I’d ever done. What a blast! As we climbed higher, the route steepened to the point where a few passages climbed overhangs via steel rungs in the rock. Soon, the exposure was massive. I was climbing in front with Harlin and David Chaundy-Smart, editor of the Canadian climbing magazine Gripped, both of whom were monkeying around on the ladders—Harlin managed a nice flag maneuver, extending his body horizontally from the cliff, with a bit of an assist from his lanyard.

Another Canadian, Jim Barr from Edmonton, was right behind me; he had never done much climbing, but he was right at home. “Can I just say,” he said for about the seventh time near the top, “this is one of the coolest things I’ve ever done.”

The view took in much of the eastern Alps, from the Eiger across to the Matterhorn and Grand Combin, to Mont Blanc and the great peaks above Chamonix. We walked down the narrow spine of the Tour d’Aï toward the mer de brouillard (sea of clouds) that had flowed into the valleys below us. Then, at the base, we walked a few more minutes to a mountain restaurant where we tucked in for—what else—more eating!

Next up: The Robbins Route. To go to the start of these reports from Switzerland, click here.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:25 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, October 03, 2007

Explosive Digestion

I always thought the idea that climbers might carry explosives on big peaks—a key plot element in that brilliant film Vertical Limit—was the ultimate load of horse puckey. But now I'm reading Bernadette McDonald's biography of Charles Houston, Brotherhood of the Rope, and what do I see on page 33? In an account of the first expedition to Mt. Crillon in Alaska, McDonald describes the team climbing "up to an overhanging cornice, for which [Brad] Washburn had brought dynamite.... Charlie [Houston] carried the caps and [Bob] Bates carried the dynamite, making sure to keep their distance from each other on the way up. But in the end it wasn't necessary: the cornice was easily penetrated."

I always thought the idea that climbers might carry explosives on big peaks—a key plot element in that brilliant film Vertical Limit—was the ultimate load of horse puckey. But now I'm reading Bernadette McDonald's biography of Charles Houston, Brotherhood of the Rope, and what do I see on page 33? In an account of the first expedition to Mt. Crillon in Alaska, McDonald describes the team climbing "up to an overhanging cornice, for which [Brad] Washburn had brought dynamite.... Charlie [Houston] carried the caps and [Bob] Bates carried the dynamite, making sure to keep their distance from each other on the way up. But in the end it wasn't necessary: the cornice was easily penetrated."

But that wasn't the end of the 1933 expedition's experiment in high-altitude pyrotechnics. When it came time to abandon their base camp, the team decided to use the explosives to blow up their latrine. "A tremendous blast sent crap high in the air.... It rained for an hour!"

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

8:51 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()