It's a nasty week in the mountain world, as two dramas are playing out with all-too-possible lethal results. On Mt. Hood, searchers are still struggling through violent storms to search for three climbers who did not return from a summit attempt last weekend. The weather on Hood is apocalyptic this week, but hopes are kept alive for at least one of the climbers, who phoned from a snow cave near the summit on Sunday and who apparently has been switching his phone on and off since then. Meanwhile, Christine Boskoff and Charlie Fowler are overdue from a two-month expedtion to central China. The two climbers, among the most experienced mountaineers in the U.S., were due to fly to Denver on December 4. There's information on how to contribute to the search effort here, and Alpinist has done a good report on the search.

It's a nasty week in the mountain world, as two dramas are playing out with all-too-possible lethal results. On Mt. Hood, searchers are still struggling through violent storms to search for three climbers who did not return from a summit attempt last weekend. The weather on Hood is apocalyptic this week, but hopes are kept alive for at least one of the climbers, who phoned from a snow cave near the summit on Sunday and who apparently has been switching his phone on and off since then. Meanwhile, Christine Boskoff and Charlie Fowler are overdue from a two-month expedtion to central China. The two climbers, among the most experienced mountaineers in the U.S., were due to fly to Denver on December 4. There's information on how to contribute to the search effort here, and Alpinist has done a good report on the search.

I remain perhaps irrationally optimistic in both cases. The climbers on Hood were experienced and, despite media reports to the contrary, reasonably prepared for the route; the fact that at least one of them was dug into a snow cave is a good sign. And Fowler has been doing walkabouts in China and Tibet for more than a decade—he rarely applies for permission or tells people exactly where he's going. He knows these little-explored mountains perhaps better than any Westerner, and has expressed his deep empathy for them and for the Tibetan people in evocative photographs like these Polaroid transfers from Kham, the area where he and Boskoff were traveling this fall, reproduced from Fowler's web site. Charlie is also a survivor of the first order, including walking (or crawling) away from a 400-foot fall off Longs Peak and a 1,000-foot fall in Asia. And so I am hopeful that he and Boskoff either saw something good and just decided to extend their trip and go for it, or that they ran into some trouble but soon will be walking back into a village in China, hungry and exhausted, with yet another amazing tale to tell.

I remain perhaps irrationally optimistic in both cases. The climbers on Hood were experienced and, despite media reports to the contrary, reasonably prepared for the route; the fact that at least one of them was dug into a snow cave is a good sign. And Fowler has been doing walkabouts in China and Tibet for more than a decade—he rarely applies for permission or tells people exactly where he's going. He knows these little-explored mountains perhaps better than any Westerner, and has expressed his deep empathy for them and for the Tibetan people in evocative photographs like these Polaroid transfers from Kham, the area where he and Boskoff were traveling this fall, reproduced from Fowler's web site. Charlie is also a survivor of the first order, including walking (or crawling) away from a 400-foot fall off Longs Peak and a 1,000-foot fall in Asia. And so I am hopeful that he and Boskoff either saw something good and just decided to extend their trip and go for it, or that they ran into some trouble but soon will be walking back into a village in China, hungry and exhausted, with yet another amazing tale to tell.

Friday, December 15, 2006

Hoping for the Best

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

8:54 AM

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

No Olympics for Ski Mountaineering

The IOC has decided not to include ski mountaineering in the 2014 Winter Olympics. For years now, the International Ski Mountaineering Council has been angling for an Olympic berth for the up-and-down ski races, which were part of the very first Winter Games. In the U.S., meanwhile, the sport is growing fast. The U.S. Ski Mountaineering Association just announced its schedule, with six races all over North America. And national champion Pete Swenson is organizing a new series in Colorado that will bring the sport closer to the Front Range and expose it to tens of thousands more skiers. Who knows where the Olympics will be in 2018, but sooner or later ski mountaineering still looks like a good bet to return to the Games.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

6:02 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Monday, December 11, 2006

Splat Calculator

This one's been around for a while, but it was new to me. The Splat Calculator was created by a climber named Dave Anderson, a professor of computer sciences at Carnegie Mellon. Or else he stole it from a 6th-grader named Parsingh who developed it for a science fair. Either way, it's a good Monday Morning Time Waster. Enter the height of a fall, and the Splat Calculator will tell you how soon you'll hit the ground and how fast you'll be going upon impact.

This one's been around for a while, but it was new to me. The Splat Calculator was created by a climber named Dave Anderson, a professor of computer sciences at Carnegie Mellon. Or else he stole it from a 6th-grader named Parsingh who developed it for a science fair. Either way, it's a good Monday Morning Time Waster. Enter the height of a fall, and the Splat Calculator will tell you how soon you'll hit the ground and how fast you'll be going upon impact.

Thus, when I was dropped precisely 9 meters from just below the ceiling of the Boulder Rock Club, I fell for 1.3552618543578767 seconds and was traveling 47.8 kph (29.7 mph) when I hit the pads. Wind resistance and the effect of my flapping arms probably throw off Anderson's calculations, but you get the idea. I remember having enough time in the air to look down, notice a bunch of holds scattered on the floor below me for route-setting, and think, "Oh, #@%&#!, I'm going to break my ankle." Instead, I rolled backward and smacked my head against a milk crate full of holds, slicing open my scalp (8 stitches) and causing a bloody mess and some wide-eyed horror among the middle-school students taking a class on the other side of the gym.

It's amazing how much thinking you can get done in 1.3552618543578767 seconds, which makes it all the more horrifying to consider a fall from, say, the top of the Nose of El Cap. The distance from there to the pines below is about 850 meters. Plunge time = 13.17 seconds. It's actually going to be quite a lot longer than that, because Anderson's formula doesn't take into account the atmospheric drag that would slow an El Cap diver nearly to terminal velocity. Either way, it's plenty of time to contemplate what's about to happen.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

6:40 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Friday, December 08, 2006

Arno's Way

A few weeks ago, my wife, Chris, and a friend took a couple of classes with Arno Ilgner, who tours the country these days doing his Warrior's Way mental-training programs for climbers. I went along to the second session, at Shelf Road, as belay slave. Chris had signed up because she was frustrated with her ability to lead climbs, which did not reflect her technical ability or strength. Basically, she got scared too easily.

A few weeks ago, my wife, Chris, and a friend took a couple of classes with Arno Ilgner, who tours the country these days doing his Warrior's Way mental-training programs for climbers. I went along to the second session, at Shelf Road, as belay slave. Chris had signed up because she was frustrated with her ability to lead climbs, which did not reflect her technical ability or strength. Basically, she got scared too easily.

Arno, who was one of the stronger American climbers of the late 1970s and early ’80s, has spent years studying various martial arts philosophies and relating them to rock climbing. From his handout: "The warrior philosophy derives from the uniquely demanding situation facing a soldier or combatant, such as a samurai, in a deadly duel. She must perform with absolute mastery and calm in the face of horrendous mortal danger."

OK, so bolt-clipping at Shelf Road isn't exactly "horrendous mortal danger." And Chris and Robin aren't exactly the type to embrace others' philosophies, whether it's a warrior's way or New Age touchy-feely action. They also didn't care for Arno's teaching style, which they felt relied too much on asking questions. ("Why don't you just tell us what you want us to know?" they both demanded at one point.) Given these obstacles, I wasn't sure how much Arno's clinic would help, but the results were profound.

I think the most valuable things Chris took away were some simple practices to help her maintain focus while leading. During Chris and Robin's leads, Arno repeatedly asked them, "Are you resting or are you climbing?" That is, when they stopped at a good hold, they should maximize the rest, study the route above them, and not dick around half-heartedly trying moves. Once they were ready to go, they should commit to keep moving until they reached the next rest stance. Sounds simple, but most of us don't climb that way; we're not 100% committed to either resting or climbing. He also taught them a simple practice before beginning a sequence of moves: Look up, look down, look up. Look up, to plan your sequence. Look down, to spot key footholds. Look up and, boom, start climbing. I can't explain the theory behind it, but it works.

Chris and Robin also did some whipper therapy, which they had been dreading. (Like a lot of people, they were much more comfortable falling indoors than out; both could count the number of real falls they'd taken outdoors in the last couple of years on one hand, or maybe even a couple of fingers.) Both of them shed some tears on the first route. But Arno's falling practice was much more effective than anything I'd seen or tried before. It wasn't just flinging yourself off, with the vain hope that this would somehow make you feel better. Instead, he taught them to assess dangers and compare them with past experiences; if the danger appeared to be no greater than ones they'd experienced before and survived, then there should be no problem. They practiced falling at the third bolt of a vertical climb, and at first they didn't even climb above the bolt. They'd just assume a climbing stance, and then I (the belayer) would pay out a teeny bit of slack, so they'd drop a couple of feet. Arno taught them good techniques for falling (arms spread, looking down, feet relaxed but ready, exhaling strongly), and had them focus on this as they fell. After each fall, he'd ask them for their observations, and, as the falls got bigger and bigger, their bottom-line observation became, "Hey, that wasn't too bad."

Results? It's been about three weeks, and Chris still thinks a lot about falling while she's climbing. But she has pushed herself very hard, indoors and out, on routes where she definitely might fall, and she's climbing more decisively than I've ever seen her. For now, at least, the lessons seem to be sticking. Anyway, I don't think she expected a miracle; she's just grateful for some progress. We're headed to Spain at the end of next week, and she is psyched to climb!

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:39 AM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, December 06, 2006

Blogroll

I don't see many newspaper blogs that I like, but Out There, written mostly by a few reporters from the Gazette in Colorado Springs, is a winner. Modestly subtitled "Colorado Springs' Path to the Outdoors," the blog will interest anyone who likes outdoor sports in the Centennial State. It's frequently updated, wide-ranging, and quirky: You never know what you'll find, like this rattler shot from today.

I don't see many newspaper blogs that I like, but Out There, written mostly by a few reporters from the Gazette in Colorado Springs, is a winner. Modestly subtitled "Colorado Springs' Path to the Outdoors," the blog will interest anyone who likes outdoor sports in the Centennial State. It's frequently updated, wide-ranging, and quirky: You never know what you'll find, like this rattler shot from today.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

4:20 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Screaming Deal

I'm biased for the American Alpine Club: I'm a past board member, I helped hire the executive director, and I do a lot of paid work for the organization. But I can say without bias that the AAC's current membership promotion is a screaming deal. New members joining the AAC can add just $30 to their dues and get a full-year subscription to Alpinist magazine (normally $46) plus a free Black Diamond Alpine Bod harness (retail $29.95). That's $46 of savings for new AAC members. And get this: If you're 28 or under, an AAC membership is just $40. There are plenty of other good reasons to join the AAC, but if you've been thinking about getting a subscription to Alpinist or buying BD's great little harness for glacier travel, now's obviously the time.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

1:39 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

New Tool for Peeping Toms?

OK, class, anyone recognize this feature on El Cap? That's the Roof and Headwall of the Salathé Wall. The truly amazing thing is that this pair of photos is actually the same photo—the one on top is just a super-enlarged version of the one below it. This much detail is possible because the photo was created with an extremely high-resolution digital camera and special software. It was posted online by an outfit called xRez. You can see more Yosemite photos, panoramas from the Sierra's East Side, cool cityscapes (that's Boston in the other pair of photos), and more at the xRez site. The company says you can see climbers in some of these photos, but I couldn't find them in a tour up the Nose and Salathé routes, though I did spot a haul bag and blue bucket hanging somewhere left of the Nose; the El Cap photo was taken in winter (you can see snow on the ledges), which explains the underpopulated walls.

OK, class, anyone recognize this feature on El Cap? That's the Roof and Headwall of the Salathé Wall. The truly amazing thing is that this pair of photos is actually the same photo—the one on top is just a super-enlarged version of the one below it. This much detail is possible because the photo was created with an extremely high-resolution digital camera and special software. It was posted online by an outfit called xRez. You can see more Yosemite photos, panoramas from the Sierra's East Side, cool cityscapes (that's Boston in the other pair of photos), and more at the xRez site. The company says you can see climbers in some of these photos, but I couldn't find them in a tour up the Nose and Salathé routes, though I did spot a haul bag and blue bucket hanging somewhere left of the Nose; the El Cap photo was taken in winter (you can see snow on the ledges), which explains the underpopulated walls.

How do they do it? The xRez site says: "The equipment required to shoot spherical panoramic imagery has typically been the use of a simple panoramic nodal head, which is manually turned to dozens of preset shooting positions, covering every possible angle within a sphere of the camera. Gigapixel level work, however, requires many hundreds of shots to be taken and demands the use of an automated motion control head which has the precision (and patience) to execute the large amount of overlapping images. The resulting shots are then stitched together in dedicated software, often taking many days of uninterrupted processing for a single image to be assembled."

How do they do it? The xRez site says: "The equipment required to shoot spherical panoramic imagery has typically been the use of a simple panoramic nodal head, which is manually turned to dozens of preset shooting positions, covering every possible angle within a sphere of the camera. Gigapixel level work, however, requires many hundreds of shots to be taken and demands the use of an automated motion control head which has the precision (and patience) to execute the large amount of overlapping images. The resulting shots are then stitched together in dedicated software, often taking many days of uninterrupted processing for a single image to be assembled."

I don't know what most of that means, but the results are stunning. xRez clearly isn't in this biz to provide better beta to climbers. They're aiming at big-dollar markets like Hollywood and Madison Avenue. Meanwhile, the samples they've put up are gaperific. There's a mind-blowing Zion landscape "coming soon" to the site, so it will be well-worth checking back.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

6:21 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Monday, December 04, 2006

The Mallorca Hype

Now that Chris Sharma has repeated another 5.15a climb, in Spain, the hype masters are again trotting out the "fact" that Sharma's deep-water solo route in Mallorca, climbed in late September, is at least 5.15a and may be 5.15b. The web site 8a.nu suggested 5.15b for the Mallorca climb, based on Sharma's 100 attempts over six visits before completing the route. (He needed fewer than 20 tries to redpoint the 5.15a La Rambla in Spain last week.) Rock & Ice said (on the cover) that Sharma's new route "is arguably the hardest climb ever done, and could reshape the sport as we know it." Inside, R&I said it's "likely the hardest rock climb in the world." Climbing said it was "a contender for the hardest single pitch in the world."

Now that Chris Sharma has repeated another 5.15a climb, in Spain, the hype masters are again trotting out the "fact" that Sharma's deep-water solo route in Mallorca, climbed in late September, is at least 5.15a and may be 5.15b. The web site 8a.nu suggested 5.15b for the Mallorca climb, based on Sharma's 100 attempts over six visits before completing the route. (He needed fewer than 20 tries to redpoint the 5.15a La Rambla in Spain last week.) Rock & Ice said (on the cover) that Sharma's new route "is arguably the hardest climb ever done, and could reshape the sport as we know it." Inside, R&I said it's "likely the hardest rock climb in the world." Climbing said it was "a contender for the hardest single pitch in the world."

The famously reticent Sharma said that his new route, shown here in a Miguel Riera photo from Desnivel, felt harder than anything he'd ever done before, even harder than his 2001 5.15a Realization. But there's a world of difference between deep-water soloing and rehearsing a route with a rope and then redpointing it. With a rope, you can stop at each bolt and carefully work out the moves and sequences for as long as you want. In deep-water soloing, you get one shot at a crux move and then you're in the drink, and you have to start over from the bottom. In this way, deep-water soloing is a beautiful return to the past traditions of ground-up ascents. As Sharma said in Climbing, deep-water soloing is "pure." But put the same route on dry land, with a bolt every six feet, and it's extremely unlikely that it would still feel as difficult.

Just because someone solos a climb doesn't mean it deserves a harder rating. A 5.12 is still 5.12, whether it's rehearsed a billion times on toprope, soloed onsight, or climbed naked with a watermelon hanging off one's harness (Charley Bentley, Vitamin H, Rifle). Sharma is obviously one of the world's best rock climbers, and it's a magnificent achievement to succeed on such a desperate climb without a rope. Sharma's experience of climbing that enormous arch in Mallorca may indeed have been his hardest and most meaningful yet. But it's just silly to suggest the arch is therefore the hardest route in the world.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:00 AM

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Sunday, December 03, 2006

Google for Runners

Back when I was a serious runner (my one-year fling with ultras in 2004-05), someone turned me on to this terrific tool for measuring routes on Google Maps. I'm suprised how many people still don't know about the Gmap "pedometer," which is great for accurately measuring the distance of running routes, such as this favorite, the Doudy Draw loop near Boulder. The tool works best on roads and highly visible trails (like bike paths in the prairie), and not so well on heavily forested trails. But I just noticed that the guy who built this thing has added a topo map overlay, which, though slow, greatly improves Gmap's usefulness for trail runners and hikers. Google Earth does this, too (Tools > Rule > Path), but I think Gmap is a simpler and more effective tool for route mapping.

Back when I was a serious runner (my one-year fling with ultras in 2004-05), someone turned me on to this terrific tool for measuring routes on Google Maps. I'm suprised how many people still don't know about the Gmap "pedometer," which is great for accurately measuring the distance of running routes, such as this favorite, the Doudy Draw loop near Boulder. The tool works best on roads and highly visible trails (like bike paths in the prairie), and not so well on heavily forested trails. But I just noticed that the guy who built this thing has added a topo map overlay, which, though slow, greatly improves Gmap's usefulness for trail runners and hikers. Google Earth does this, too (Tools > Rule > Path), but I think Gmap is a simpler and more effective tool for route mapping.

Marathoners and ultrarunners say you're supposed to plan workouts by time and effort, not by distance, but it's still fun to know exactly how far you went. This tool tells you down to the ten-thousandth of a mile—a little over 6 inches.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:47 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Seven Summits Skied (For Real)

Slovenian Davo Karnicar skied from the summit of Mt. Vinson in Antarctica this week, thus becoming the first person to do complete ski descents of the Seven Summits. Karnicar, 44, was the first and only person to make a complete ski descent of Mt. Everest, on the south side, in October 2000. He also has done a complete ski descent of Annapurna.

Slovenian Davo Karnicar skied from the summit of Mt. Vinson in Antarctica this week, thus becoming the first person to do complete ski descents of the Seven Summits. Karnicar, 44, was the first and only person to make a complete ski descent of Mt. Everest, on the south side, in October 2000. He also has done a complete ski descent of Annapurna.

American Kit DesLauriers was hailed last month as the first woman to ski the Seven Summits. But in the mind of most purists, her two-day ski from the summit of Everest, while laudable, can't be counted as a ski descent of the mountain. DesLauriers earned headlines and interviews across the country. Karnicar? A search of Google News this morning revealed not a single story.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:38 AM

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Separated at Birth?

Does anyone else see it? That's a young Jim Bridwell on the left and Tommy Caldwell on the right. Is it just a coincidence that two of the most influential American climbers of their respective generations looked so much alike? Or are deeper forces at work?

Does anyone else see it? That's a young Jim Bridwell on the left and Tommy Caldwell on the right. Is it just a coincidence that two of the most influential American climbers of their respective generations looked so much alike? Or are deeper forces at work?

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

2:24 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Gobsmacking

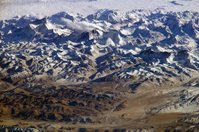

Views of the Earth from space are nothing new, but this one of the Everest region in the Himalaya blew me away when I stumbled upon it today. That's Everest in the middle, Makalu on the left, the barren Tibetan hills in the foreground, and Nepal in the clouds in the back. You can get to any even bigger mosaic of images from space depicting an 80-mile span of the high Himalaya through this NASA page, but you'll need a huge monitor to do it justice.

Views of the Earth from space are nothing new, but this one of the Everest region in the Himalaya blew me away when I stumbled upon it today. That's Everest in the middle, Makalu on the left, the barren Tibetan hills in the foreground, and Nepal in the clouds in the back. You can get to any even bigger mosaic of images from space depicting an 80-mile span of the high Himalaya through this NASA page, but you'll need a huge monitor to do it justice.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

12:27 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Monday, November 20, 2006

Where Do I Clip In?

These photos have been bouncing around the internet in recent days without being identified: This is the Changkong zhandao "plank path" on Huangshan peak, a Unesco World Heritage site in east-central China. The plank path is a sort of via ferrata across the near-vertical granite slabs of the south peak. Not too worried about litigation here, are we?

These photos have been bouncing around the internet in recent days without being identified: This is the Changkong zhandao "plank path" on Huangshan peak, a Unesco World Heritage site in east-central China. The plank path is a sort of via ferrata across the near-vertical granite slabs of the south peak. Not too worried about litigation here, are we?

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:40 PM

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Friday, November 17, 2006

Skiing the Eiger (Sort of)

More madness with parachutes! Check out this short helmet-cam video of "speed riding" the Eiger. The guy screams down the snowy western flank of the peak, bumping off the occasional slab of limestone, and then swings right and hucks over the north face. OK, yeah, he's paragliding, but this is no tourist flight: The guy turns the Eiger into a bump run, his skis slicing off the tops of snow patches glued to the north face. This run gives new meaning to the term "rock skis."

More madness with parachutes! Check out this short helmet-cam video of "speed riding" the Eiger. The guy screams down the snowy western flank of the peak, bumping off the occasional slab of limestone, and then swings right and hucks over the north face. OK, yeah, he's paragliding, but this is no tourist flight: The guy turns the Eiger into a bump run, his skis slicing off the tops of snow patches glued to the north face. This run gives new meaning to the term "rock skis."

But wait, there's more! This video has helicopter footage of the Eiger descent. And this one shows a speed-riding descent of Mont Blanc, the highest peak in Western Europe. (If you have a fast enough connection, skip to the middle for the best stuff.) What will these kids think of next!

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

6:58 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Wingsuit Madness

Remember when B.A.S.E. jumping seemed crazy? Compared with flying a wingsuit, simply jumping off cliffs with a parachute is like a gentle ride down an Otis elevator. Check out this amazing video of wingsuit-flying wingnuts jumping off the north face of the Eiger and other huge European cliffs. (One of these wingnuts is an old friend, the climber and SuperTopo magnate Chris McNamara.) Amazing to see how much forward distance they cover, how close they fly along the walls, and how late they wait to pop the chute. A good pilot can fly 90 to 120 mph and achieve a glide ratio of 2.5 to 1—that means flying about 3 miles straight ahead in a jump off the Eiger. Jeezum crowbar! This has gotta be one of the wildest videos I've ever seen—maybe it's old hat if you've seen a lot of this stuff, but to me it was a real mind-bender.

Remember when B.A.S.E. jumping seemed crazy? Compared with flying a wingsuit, simply jumping off cliffs with a parachute is like a gentle ride down an Otis elevator. Check out this amazing video of wingsuit-flying wingnuts jumping off the north face of the Eiger and other huge European cliffs. (One of these wingnuts is an old friend, the climber and SuperTopo magnate Chris McNamara.) Amazing to see how much forward distance they cover, how close they fly along the walls, and how late they wait to pop the chute. A good pilot can fly 90 to 120 mph and achieve a glide ratio of 2.5 to 1—that means flying about 3 miles straight ahead in a jump off the Eiger. Jeezum crowbar! This has gotta be one of the wildest videos I've ever seen—maybe it's old hat if you've seen a lot of this stuff, but to me it was a real mind-bender.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:29 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Monday, November 13, 2006

Yummm.... Spindrift!

Greg Sievers ducks for cover on Sunday as he starts the crux fourth pitch of Pipe Organ (far-right variation), Glacier Gorge, Rocky Mountain National Park.

Greg Sievers ducks for cover on Sunday as he starts the crux fourth pitch of Pipe Organ (far-right variation), Glacier Gorge, Rocky Mountain National Park. Pipe Organ is the route to the right of the popular All Mixed Up (on the left of the picture, with climbers on it). We climbed two pitches to a ledge system, did a fairly sketchy full-rope traverse to the right, and then climbed a dihedral with very thin ice to reach thicker ice and exit through a short rock band.

Pipe Organ is the route to the right of the popular All Mixed Up (on the left of the picture, with climbers on it). We climbed two pitches to a ledge system, did a fairly sketchy full-rope traverse to the right, and then climbed a dihedral with very thin ice to reach thicker ice and exit through a short rock band.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

8:23 AM

4

comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

Everest + Gift of Gab = $$$

Ever wonder how much money celebrity adventurers get for doing those corporate speaking gigs? Actually, not very many climbers and skiers make anything—most of the climbers I know rake in a few hundred bucks and some free beer, at best, at the shows they do, and they often give the proceeds to the Access Fund or the AAC. But for a few people there's real money in delivering 45 minutes of after-dinner inspiration and bon mots to the salarymen, along with some stirring images of climbing ladders over crevasses.

The big money is on Everest, where even the faintest stardom commands a healthy speaking fee. A quick, unscientific survey of speakers' bureaus shows that Everest vets Ed Viesturs, Jim Whittaker, David Breashears, and Peter Hillary all ask $10,000 to $20,000 per speech. Sharon Wood, the first North American woman to climb Everest, might be available for as little as $5,000, but Stacy Allison, the first American, gets $20,000 to $30,000, more than all the guys except back-from-the-dead Everest ’96 survivor Beck Weathers. In fact, triumphing over adversity trumps fully abled success every time. Aron Ralston's speaking fee went from 0 to as high as $50,000 after he lopped off his arm in Blue John Canyon. Blind climber Erik Weihenmayer commands $30,000 to $50,000 for his inspirational talks.

Rock climbing, meanwhile, is too hard to explain and too boring to watch to make it big in the corporate world. The only highly marketable speaker whose claim to fame was primarily rock climbing was the late Todd Skinner (fee range: $10,000 to $20,000). In any case, we all know that adventure sports pale in comparison to mainstream celebrity when it comes to bringing home the bacon. Lance Armstrong's fee for a single speaking gig? $150,000 and up.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:32 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Monday, November 06, 2006

G is for Grovel

Kelly Cordes, who always has something to say about—well, about just about anything—filled me in on an alternative grading system while we were walking down from Eldorado Canyon's upper West Ridge yesterday. The G System, he explained, is the most useful way to rate mixed alpine climbs, because it gets at the hardest and sketchiest part of alpine climbing: snowed-up, thin-or-no-ice rock climbing. The kind of climbing where nothing sticks, there are no holds to grab, and pro is nonexistent, and the keys to success are determination, boldness, and the ability to oonch up slick, snowy granite. The G stands for "groveling". Turns out that a lot of climbers who are extremely talented when measured by the Yosemite decimal system or water-ice grades or even the M scale for modern mixed climbing can't always master G climbing. "I know people who are solid M10 climbers who get shut down by G4 groveling," Cordes says. Never mind that there's no way to explain what G4 feels like. If you have to ask, you haven't done it.

Cordes has done big routes with some of the best alpine climbers in the U.S., Jonny Copp and Josh Wharton among them. But he says the best G-climber he's ever tied in with, hands down, is the relatively unknown Scott DeCapio. "It's unbelievable how quickly Scotty can climb that stuff," he says. DeCapio served a rugged apprenticeship: He lived in his VW Fox hatchback for five years, traveling around to climb. He and Cordes have done some great new routes and speedy ascents in Alaska, and right now they're mulling over the right overseas project to attempt next summer or fall. A climb, that is, with a G-rating that won't get parental approval.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

4:21 PM

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Lessons from Todd's Death

Here it is: The first round of my Todd Skinner Memorial Gear Dump. After Todd's death from harness failure last week, I started going through my old gear with a newly suspicious eye. I know for a fact that the slings on those Friends are 20 years old! I almost never use them—they're third- or fourth-string units for Indian Creek cracks—but why take chances? (And no, I'm not dumping the old cams, just the slings. Some things are just too hard for a Scotch Yankee to do.) Some of those quickdraws are probably 15 to 20 years old. One of the daisy chains is probably pretty good, but the other was retired a long time ago; I just use it as a dog leash now and then, but we've got plenty of other leashes—what if someone mistakenly assumed this was safe to use for climbing? That beater harness is really embarassing: We kept it around to loan to friends who might not have a harness! With friends like us...

Here it is: The first round of my Todd Skinner Memorial Gear Dump. After Todd's death from harness failure last week, I started going through my old gear with a newly suspicious eye. I know for a fact that the slings on those Friends are 20 years old! I almost never use them—they're third- or fourth-string units for Indian Creek cracks—but why take chances? (And no, I'm not dumping the old cams, just the slings. Some things are just too hard for a Scotch Yankee to do.) Some of those quickdraws are probably 15 to 20 years old. One of the daisy chains is probably pretty good, but the other was retired a long time ago; I just use it as a dog leash now and then, but we've got plenty of other leashes—what if someone mistakenly assumed this was safe to use for climbing? That beater harness is really embarassing: We kept it around to loan to friends who might not have a harness! With friends like us...

I'm sure most of this stuff would be just fine. Kolin Powick, quality assurance manager at Black Diamond, did an amazing series of tests on "distressed" belay loops following Todd's death. You've got to see this. He found that loops sliced 50 percent and even 75 percent of the way through retained much of their strength. He cut bar tacks and abraded the stitching and webbing so seriously that most climbers would immediately junk their harnesses if they looked this bad. The result? Still strong. Makes me think something (chemicals? UV damage?) must have seriously compromised Todd's belay loop, maybe even the day before his fatal rappel. Likely it was a combination of age, wear, and some mystery factor. The loop was found at the scene and no doubt will be analyzed. Meanwhile, I figure, why risk it? This junk is just cluttering up my gear room anyway, and I'm sure I'll find more like this when I dig deeper into the boxes. Today's trash day on my street, and it's time to toss this pile.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

8:13 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

Yamabushi Slide Show

In mid-October, the day before I climbed at Yamnuska, Will Gadd completed his longtime project to create what's now the hardest route on the big limestone cliff near Canmore, Alberta: Yamabushi (8 pitches, 5.13a). There's a really good annotated slide show about the climb on the Arc'teryx web site. Gadd and photographer Cory Richards, who took this shot of the crux second pitch as well as the others in the show (and also helped Gadd work on the route this fall) will be doing some live slide shows in coming months. Catch it if you can: Should be really good.

In mid-October, the day before I climbed at Yamnuska, Will Gadd completed his longtime project to create what's now the hardest route on the big limestone cliff near Canmore, Alberta: Yamabushi (8 pitches, 5.13a). There's a really good annotated slide show about the climb on the Arc'teryx web site. Gadd and photographer Cory Richards, who took this shot of the crux second pitch as well as the others in the show (and also helped Gadd work on the route this fall) will be doing some live slide shows in coming months. Catch it if you can: Should be really good.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

10:16 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

Messner's Feats and Feets

The lead story in the November issue of National Geographic is about the one and only Reinhold Messner. Although the article has some very interesting info about Messner's childhood, I found myself wondering, "Why now?" I suppose the general public hasn't read much about the latest Messner drama: the discovery of the body of his lost brother, Gunther, killed on Nanga Parbat in 1970. The most striking photo in the article is a double-truck spread of Messner's feet. He lost seven toes to frostbite after Nanga Parbat, and the feet are stunted and strange but not really shocking; I imagine them almost like hobbit feet without the hair. Click here to see a gallery of Messner photos by photographer Vincent J. Musi, including the fabled feet, as well as archival images.

The lead story in the November issue of National Geographic is about the one and only Reinhold Messner. Although the article has some very interesting info about Messner's childhood, I found myself wondering, "Why now?" I suppose the general public hasn't read much about the latest Messner drama: the discovery of the body of his lost brother, Gunther, killed on Nanga Parbat in 1970. The most striking photo in the article is a double-truck spread of Messner's feet. He lost seven toes to frostbite after Nanga Parbat, and the feet are stunted and strange but not really shocking; I imagine them almost like hobbit feet without the hair. Click here to see a gallery of Messner photos by photographer Vincent J. Musi, including the fabled feet, as well as archival images.

Like most Americans, I've subscribed to National Geographic off and on for most of my life, and in my view it's gotten much better in recent years. The pictures remain excellent, and the magazine is making a real push to improve the quality of its feature writing (with varying success) and to liven up the overall content. I particularly like the front of the book in recent editions, especially a provocative monthly Q&A interview that typically runs six pages or so—highly unusual for an article in the front of a magazine. National Geographic also has been more successful than most at integrating the print mag with its online content—of course, National Geographic also has about 100 times more resources than most magazines do. Still, I think it's great that a hoary old institution like the Big Yellow Book is working hard to stay fresh.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

6:00 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Sunday, October 29, 2006

Department of Scary Critters

Jason Poole, a superb adventure racer and ultrarunner from Colorado, got a nasty surprise at the World Rogaining Championships in New South Wales, Australia, this month. About two and a half hours into the 24-hour race, he was bitten by an Australian brown snake, one of the deadliest snakes on that continent full of deadly critters. Poole and his teammate, Adam Chase, hiked several miles to the road and made it to the hospital, where he was pumped full of meds and saved. Poole was wearing gaiters and apparently only one of the snake's fangs punctured his skin—doctors said that if both fangs had penetrated his ankle, Poole never would have made it out of the bush.

Jason Poole, a superb adventure racer and ultrarunner from Colorado, got a nasty surprise at the World Rogaining Championships in New South Wales, Australia, this month. About two and a half hours into the 24-hour race, he was bitten by an Australian brown snake, one of the deadliest snakes on that continent full of deadly critters. Poole and his teammate, Adam Chase, hiked several miles to the road and made it to the hospital, where he was pumped full of meds and saved. Poole was wearing gaiters and apparently only one of the snake's fangs punctured his skin—doctors said that if both fangs had penetrated his ankle, Poole never would have made it out of the bush.

Rogaining, by the way, is a super-fun variant of orienteering. Instead of navigating from point A to B to C, you're given a map with dozens of checkpoints, called controls, scattered everywhere. The controls are worth more points the harder they are to reach. You plan your own route and try to bag as many points as you can within a set time period. (At major events, it's 24 hours and the map covers more than 100 square miles.) A friend and I ran in the last world championships, in eastern Arizona, in 2004, and I wrote a feature story about this amazing experience. (Read it here.) Don't get the wrong idea: I'm definitely

Rogaining, by the way, is a super-fun variant of orienteering. Instead of navigating from point A to B to C, you're given a map with dozens of checkpoints, called controls, scattered everywhere. The controls are worth more points the harder they are to reach. You plan your own route and try to bag as many points as you can within a set time period. (At major events, it's 24 hours and the map covers more than 100 square miles.) A friend and I ran in the last world championships, in eastern Arizona, in 2004, and I wrote a feature story about this amazing experience. (Read it here.) Don't get the wrong idea: I'm definitely  no endurance animal. Rogaining is such an obscure sport that anyone can enter the world championships. In fact, although my partner and I had been orienteering for years, this was our very first rogaine. The photos here show my teammate, Dave Goldstein, at the 2004 championships, striding confidently at sunset, and then, the next morning, an utterly destroyed Dave taking a catnap while one of the real competitors (from the Czech Republic) punches a control. At least we didn't see any snakes.

no endurance animal. Rogaining is such an obscure sport that anyone can enter the world championships. In fact, although my partner and I had been orienteering for years, this was our very first rogaine. The photos here show my teammate, Dave Goldstein, at the 2004 championships, striding confidently at sunset, and then, the next morning, an utterly destroyed Dave taking a catnap while one of the real competitors (from the Czech Republic) punches a control. At least we didn't see any snakes.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:52 AM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Friday, October 27, 2006

Choss Master

I went to a slide show by Mike Anderson the other night, covering his seven, count ’em, first free ascents of big sandstone walls in Zion National Park in the past couple of years. He's a humble, funny speaker, the photos are excellent, and the show is well worth seeing if you get the chance.

I particularly liked one comment Mike made, only half joking, about training for traditional climbing: "All the sport climbers want to climb super-steep stuff like at Rifle, but it has no practical application," he said. "Vertical sport climbing is what you do to train for trad climbing: Smith Rock, Penitente, Shelf Road. Weird features, using your feet. It's kind of a lost art." I feel the same way about training at the gym: I try to force myself to stay mostly on vertical and slightly overhanging routes. Crimping and smearing on tiny, greasy  plastic holds isn't as much fun as monkeying around on those big cave climbs, but it's a lot more like the outdoor climbs the vast majority of us do.

plastic holds isn't as much fun as monkeying around on those big cave climbs, but it's a lot more like the outdoor climbs the vast majority of us do.

Hey, Mike: Free this! No amount of training is likely to allow a free ascent of the Shadow Line, the Zion route in this picture—at least not until it's been beaten out by more than the two ascents I know of...

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:42 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Thursday, October 26, 2006

The Harness Broke

Although an official investigation remains to be completed, it appears increasingly—shockingly—likely that a broken belay loop on Todd Skinner's harness caused his death while rappelling from Leaning Tower. Skinner's partner, Jim Hewett, is quoted extensively in an excellent article in today's San Francisco Chronicle. "[The harness] was actually very worn," Hewett told the paper. "I'd noted it a few days before, and he was aware it was something to be concerned about." The story continued, "Friends of Skinner said he had ordered several new harnesses but they hadn't yet arrived in the mail. On Monday's climb, Hewett said the belay loop snapped while Skinner was hanging in midair underneath an overhanging ledge."

Unbelievable. I spent the last two days refuting these rumors to friends who called to speculate about the cause of Todd's accident. No way a belay loop breaks, I said. No way Todd would be using an old, tatty harness—he was too experienced, too careful. He could get free harnesses! I still wonder if somehow the loop was compromised: cut on an edge or tainted with some corrosive substance. But I know this for sure: Like thousands of other climbers this morning, I'm headed down to the gear closet to have a look through my kit. I'm not assuming anything is "good enough" anymore.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

5:50 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Ski Descent of Everest? Not Exactly

Kit DesLauriers is being hailed as the first woman to ski Mt. Everest, or, in the more carefully crafted reports, the first woman to ski "from the summit" of Everest. On October 18, DesLauriers climbed to the top with her husband, Rob, and other members of a team from Berg Adventures, and then she, Rob, and Jimmy Chin started skiing from the top. However, in view of conditions on the route, they decided to rappel the Hillary Step, then climbed over the South Summit and down to the South Col. They spent the night there, skied the Lhotse Face the next morning, and then skied and downclimbed the rest of the way to base camp. This is certainly a great personal achievement, and DesLauriers and the team should be psyched about what they accomplished and proud that they made the decision to put safety over personal glory by removing their skis when the conditions were too dangerous. However, Outside's web site is trumpeting that DesLauriers is the "first woman to ski the Seven Summits and the first American to ski Everest," and is plugging a big story in January. NPR ran an interview with "the first person to ski the Seven Summits."

The DesLauriers-Chin descent was far from a complete, continuous descent of the mountain, a feat that was first accomplished by the Slovenian Davo Karnicar in 2000. Karnicar skied the South Col route, including the Hillary Step, the steep slopes on one side of the South Summit, the Lhotse Face, and a dangerous bypass to the Khumbu Icefall low on the route, all the way to base camp in less than five hours. The following year, Marco Siffredi snowboarded the Norton Couloir on the north side of the peak. These two men set the standard for riding Everest.

Again, this isn't to take anything away from DesLauriers' accomplishment. And the DesLauriers have been completely straightforward about what they did and didn't do, telling NPR, for example, that "it's important to be clear" that they didn't do a complete ski descent—they skied 6,000 feet of the 8,500 feet of skiable vertical on the mountain. It's just unfortunate that the mainstream media (and many specialty outlets) have got it wrong. There's still a big goal waiting out there for the first woman to make a complete ski or snowboard descent of Everest. For that matter, Karnicar hopes to complete the Seven Summits sometime in the next few months by skiing Mt. Vinson in Antarctica. In the minds of most skiing purists, he then would be the first to ski the Seven Summits. It would be a shame to see such achievements diminished because the media had declared that someone else came "first."

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

9:48 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

RIP

There's a wonderful tribute thread on Supertopo.com for Todd Skinner, who died Monday in an accident on Leaning Tower in Yosemite. Read it if you didn't know the man or wonder why people are talking about him. Striking to me are the kind words from certain Valley regulars who were once outraged at Skinner and his importation of new-wave free-climbing tactics to Yosemite during the 1980s. I guess death silences critics, or maybe it's just that Skinner's broad smile and relentless enthusiasm finally won out. RIP, Todd, though resting is hardly what we'd come to expect from you. Maybe "redpoint in progress."

There's a wonderful tribute thread on Supertopo.com for Todd Skinner, who died Monday in an accident on Leaning Tower in Yosemite. Read it if you didn't know the man or wonder why people are talking about him. Striking to me are the kind words from certain Valley regulars who were once outraged at Skinner and his importation of new-wave free-climbing tactics to Yosemite during the 1980s. I guess death silences critics, or maybe it's just that Skinner's broad smile and relentless enthusiasm finally won out. RIP, Todd, though resting is hardly what we'd come to expect from you. Maybe "redpoint in progress."

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

6:44 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Thursday, October 19, 2006

Stanley Peak

John Harlin and I were super-keen to climb a peak during our visit to Banff, and fortunately the autumn snows had been light and the weather on Saturday was excellent. While UIAA delegates argued over the future of the organization in a Banff conference room and AAC board members headed to cliffs around Canmore for some cragging, John and I got up in the dark to head to Stanley Peak, about half an hour away from Banff. We didn't exactly get an alpine start, leaving the

John Harlin and I were super-keen to climb a peak during our visit to Banff, and fortunately the autumn snows had been light and the weather on Saturday was excellent. While UIAA delegates argued over the future of the organization in a Banff conference room and AAC board members headed to cliffs around Canmore for some cragging, John and I got up in the dark to head to Stanley Peak, about half an hour away from Banff. We didn't exactly get an alpine start, leaving the  trailhead at 7:45 a.m., but we figured we could finish a route on Stanley's north face and still get back to Banff for the Alpine Club of Canada's centennial festivities. The sun rose as we hiked past the Stanley Headwall, its notorious ice climbs only showing smidges of ice, and after a couple of hours we reached the base of the glacier, which had iron-hard, centuries-old ice at the base but a healthy covering of snow above.

trailhead at 7:45 a.m., but we figured we could finish a route on Stanley's north face and still get back to Banff for the Alpine Club of Canada's centennial festivities. The sun rose as we hiked past the Stanley Headwall, its notorious ice climbs only showing smidges of ice, and after a couple of hours we reached the base of the glacier, which had iron-hard, centuries-old ice at the base but a healthy covering of snow above.

Living in Colorado, I have easy access to abundant and diverse climbing, but the one thing that's missing is glacial mountaineering, so it was great fun for me just to get the chance to rope up and zig-zag through some crevasses, leaping the odd snow bridge. Guides' reports on the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides site had commented on the abundance and size of new crevasses on Rockies glaciers, and though we had no basis for comparison we found the Stanley Glacier to be surprisingly complex. The schrund on our chosen route, the Waterman Couloir, was big but pretty easy to pass on the right. Above, it looked like a short, simple snow gully, but the couloir was at least 1,000 feet long and took us more than two hours to climb, even though we moved together. The snow covering was thin, and the ice underneath was glassy, brittle, and super-hard, and it was filled with hidden shards of limestone and shale.

mountaineering, so it was great fun for me just to get the chance to rope up and zig-zag through some crevasses, leaping the odd snow bridge. Guides' reports on the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides site had commented on the abundance and size of new crevasses on Rockies glaciers, and though we had no basis for comparison we found the Stanley Glacier to be surprisingly complex. The schrund on our chosen route, the Waterman Couloir, was big but pretty easy to pass on the right. Above, it looked like a short, simple snow gully, but the couloir was at least 1,000 feet long and took us more than two hours to climb, even though we moved together. The snow covering was thin, and the ice underneath was glassy, brittle, and super-hard, and it was filled with hidden shards of limestone and shale.  I smacked my picks dozens of times on hidden rocks, and later discovered that I had bent the tip of one of them, which I'd like to think is an explanation for why my left hand was getting so tired near the top.

I smacked my picks dozens of times on hidden rocks, and later discovered that I had bent the tip of one of them, which I'd like to think is an explanation for why my left hand was getting so tired near the top.

(By the way, Black Diamond sells three versions of its picks for the Viper tools I use: Don't buy the Laser pick, which is sold for "pure ice," because almost no ice climb is that "pure." You'll end up hitting rock sooner or later, and I bent the tips of two Lasesr picks in a single season. OK, maybe I overswing a bit, but I'll only buy the tougher Fusion or Titan picks from now on.) John amazes me with his fitness. He has spent most of the last year in Mexico, working on a book, with almost no opportunities to get into the mountains. Yet he kicked my ass on this 5,000-vertical-foot day, and he seemed unfazed by 1,000 feet of ice climbing. Some of it is due to sheer enthusiasm—he relishes each of his limited days in the hills—but he also stays honed by making daily life a workout. He says escalators are a "pet peeve" and never uses them; he takes the stairs if he has less than seven flights to go up or down. In the airport on the way home, I watched him work his calves at the counter by our gate, rocking up onto his toes over and over, and doing curls with his 20-pound briefcase as we waited in line for security. Whatever he's doing, it seems to work.

John amazes me with his fitness. He has spent most of the last year in Mexico, working on a book, with almost no opportunities to get into the mountains. Yet he kicked my ass on this 5,000-vertical-foot day, and he seemed unfazed by 1,000 feet of ice climbing. Some of it is due to sheer enthusiasm—he relishes each of his limited days in the hills—but he also stays honed by making daily life a workout. He says escalators are a "pet peeve" and never uses them; he takes the stairs if he has less than seven flights to go up or down. In the airport on the way home, I watched him work his calves at the counter by our gate, rocking up onto his toes over and over, and doing curls with his 20-pound briefcase as we waited in line for security. Whatever he's doing, it seems to work. Stanely is a decent-sized Rockies peak at 3,155 meters (10,351 feet), and from the top we could see Assiniboine, Temple, and thousands of other peaks—I've got to get back here! The descent was long and complicated. We hadn't brought the guidebook, but I'm not sure it would have helped anway. The descent to the east, down a snow gully adjacent to an icefall, now appears choked with crevasses and ice walls. We ended up downclimbing a gully farther east that could easily have been a climb. Two routes in one day! It was a 12-hour round trip to the car, and we were sure we'd missed the Alpine Club of Canada's

Stanely is a decent-sized Rockies peak at 3,155 meters (10,351 feet), and from the top we could see Assiniboine, Temple, and thousands of other peaks—I've got to get back here! The descent was long and complicated. We hadn't brought the guidebook, but I'm not sure it would have helped anway. The descent to the east, down a snow gully adjacent to an icefall, now appears choked with crevasses and ice walls. We ended up downclimbing a gully farther east that could easily have been a climb. Two routes in one day! It was a 12-hour round trip to the car, and we were sure we'd missed the Alpine Club of Canada's  centennial dinner, but such events apparently start later in Canada than at home: We sat down at 9 p.m., just in time for the first course. John stayed up dancing and carousing until after 3 a.m. I went to bed at midnight, hoping it would rain the next day so we wouldn't have to climb again. But it was just good enough to go to Yamnuska.

centennial dinner, but such events apparently start later in Canada than at home: We sat down at 9 p.m., just in time for the first course. John stayed up dancing and carousing until after 3 a.m. I went to bed at midnight, hoping it would rain the next day so we wouldn't have to climb again. But it was just good enough to go to Yamnuska.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

6:30 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Yamnation!

I made a quick trip to Banff last weekend for various American Alpine Club and Alpine Club of Canada events, and we were so lucky with the late-fall weather that I ended up skipping most of the meetings and climbing three days in a row. On Friday, John Harlin (editor of the American Alpine Journal) and I did a short route on Yamnuska, Alberta's storied 1,000-foot limestone cliff. The rock on Yam is better than that on many Canadian Rockies peaks, but it's not perfect. Our three-pitch route, Smeagol (5.9) had one junky pitch, one decent pitch, and one superb steep pitch at the top. It wouldn't get the two stars the guidebook gives it in Eldorado Canyon or Yosemite, but it was a great introduction to the cliff on a gorgeous Indian Summer day.

I made a quick trip to Banff last weekend for various American Alpine Club and Alpine Club of Canada events, and we were so lucky with the late-fall weather that I ended up skipping most of the meetings and climbing three days in a row. On Friday, John Harlin (editor of the American Alpine Journal) and I did a short route on Yamnuska, Alberta's storied 1,000-foot limestone cliff. The rock on Yam is better than that on many Canadian Rockies peaks, but it's not perfect. Our three-pitch route, Smeagol (5.9) had one junky pitch, one decent pitch, and one superb steep pitch at the top. It wouldn't get the two stars the guidebook gives it in Eldorado Canyon or Yosemite, but it was a great introduction to the cliff on a gorgeous Indian Summer day. On Sunday, John and I returned to Yam with Phil Powers, executive director of the AAC, hoping to do a full-length route. It was early afternoon by the time we got there and the top of the cliff was in mist, but we figured we could rappel at any time and might as well just go for it. My guidebook weighed about a pound, and we were debating whether and how to carry it when someone had a brilliant idea: Two of us were planning to carry digital cameras anyway,

On Sunday, John and I returned to Yam with Phil Powers, executive director of the AAC, hoping to do a full-length route. It was early afternoon by the time we got there and the top of the cliff was in mist, but we figured we could rappel at any time and might as well just go for it. My guidebook weighed about a pound, and we were debating whether and how to carry it when someone had a brilliant idea: Two of us were planning to carry digital cameras anyway,  and so we just snapped pictures of the relevant guidebook pages and then zoomed in on them when we needed to figure out where to go en route. Worked great!

and so we just snapped pictures of the relevant guidebook pages and then zoomed in on them when we needed to figure out where to go en route. Worked great!

Our route (Kahl Wall, 8 pitches, 5.10a) was wandering and ledgy at the bottom, but the upper half was excellent, with steep face and corner climbing on great rock.  We got a bit of rain and shivered in our light jackets, and some graupel fell during the last pitch, but we made it to the top and the heavy rain didn't start until we had nearly finished the descent. The next morning it was snowing hard in Calgary. Snuck in another one! Yam reminded me of climbing in the Dolomites (perhaps my favorite destination in the world), and I loved it despite the

We got a bit of rain and shivered in our light jackets, and some graupel fell during the last pitch, but we made it to the top and the heavy rain didn't start until we had nearly finished the descent. The next morning it was snowing hard in Calgary. Snuck in another one! Yam reminded me of climbing in the Dolomites (perhaps my favorite destination in the world), and I loved it despite the  grueling approach march. I hope to return someday a bit earlier in the season and try one or two of the harder routes.

grueling approach march. I hope to return someday a bit earlier in the season and try one or two of the harder routes.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:30 AM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Sunday, October 08, 2006

Send It!

Canada Post issued a stamp in July to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Alpine Club of Canada. This made me curious about other stamps related to the mountains. I found a the mother lode at the Dutch online stamp dealer Postbeeld.com.

Canada Post issued a stamp in July to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Alpine Club of Canada. This made me curious about other stamps related to the mountains. I found a the mother lode at the Dutch online stamp dealer Postbeeld.com.

Not surprisingly, nationalism is big in stamps. Examples, clockwise from top left: 1982 stamp commemorating a Soviet Union expedtion to Mt. Everest; a 2004 edition celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Italian team's first ascent of K2; and a Chinese stamp from 1965, marking the 1964 first ascent of Shishapangma. Strangely, Bhutan, which has tightly restricted access to its mountains, issued a stamp in 1982 celebrating mountaineering. Skiing is widely represented, too. This 2004 Austrian stamp cheers on the Herminator. Want to see more? Go to Postbeeld and search for "mountain climbing" or "skiing."

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

3:59 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()