We had walked along the base of the Eiger, and now we were going to ride a train right through it. This was the famous Jungfrau Railway, an engineering marvel completed in 1912. From the Eigergletscher Station at the base of the west face, the train bores through the mountain, just inside the nordwand. Soon the famed Stollenloch window, scene of many Eiger rescues and bailouts, opens onto the north face. Actually, the train doesn’t stop there but continues to a viewing gallery farther east. Still, the view from the gallery was astonishing enough when I thought of what our Grindelwald host had told us: Skiers sometimes climb out the Stollenloch, rappel or jump onto the snow, and ski the lower third of the face. “It’s not authorized, but people do it,” Martin said.

The train’s seven-kilometer tunnel arcs to the south, still inside the mountain, and stops again at the Eismeer Station, where another gallery offers superb views to the Lower Grindelwald Glacier and the surrounding peaks. Then it tunnels straight under the Mönch, a 4,000-meter peak, and comes to a stop, deep under the glacier, at the Jungfraujoch, the 11,400-foot saddle between the Mönch and the Jungfrau. Engineers originally had hoped to carry on to the summit of the 13,642-foot Jungfrau, but wiser minds (and World War I) intervened.

More than 8,000 feet above Grindelwald, the Jungfraujoch is a sight to behold. It’s an enormous complex (the schematic in my brochure looks like a blueprint for a nuclear submarine or NORAD’s underground HQ), with a bewildering array of restaurants and tourist attractions. More than 600,000 tourists visit the Jungfraujoch each year, and many of them are Asian—the canny Swiss have responded with a restaurant called Bollywood and noodle bowls on sale at the cafeteria alongside the hot chocolate and croissants. On one level is the Ice Palace, a series of slippery-floored corridors decorated with carved penguins and the like; on another is a Swiss watch shop, where you can buy a timepiece authenticated as being sold at the “Top of Europe”—which is patently a falsehood since the neighboring peaks, to say nothing of Mont Blanc or Mt. Elbrus, are, to even the most inexperienced eye, obviously higher. Still, this is likely the highest point most of the hypoxic tourists have ever reached. Inside, semi-conscious women in saris and men in baggy pants sat collapsed in corners and poking listlessly at their food, ignoring the view.

And what a view! After riding an elevator to the Sphinx viewing platform at 11,760 feet, we gaped at the surrounding mountains, from the nearby Mönch and Jungfrau (two of Europe’s most popular 4,000-ers because of the easy rail access) to distant Monte Rosa and Mont Blanc. Below us swept the Aletsch Glacier, the longest in the Alps.

We escaped the tourists for a time by walking about 40 minutes across the flat glacier from the foot of the Jungfrau to a hut at the base of the Mönch. Here we ate a lunch of yet another cheesy käseschnitte (never enough!) and a drink called holdrio, a spiked rose-hip tea that we quickly renamed hootenanny. Then it was time to catch the train back down, so we scurried back across the glacier to rejoin the madness at the Jungfraujoch, where John discovered the ultimate Alpine accessory: an ATM overlooking the Aletsch Glacier.

Actually, I quite enjoyed the weird scene at the Jungfraujoch. The train and the tourist complex on top make for a hyper-expensive outing that has almost nothing to do with mountaineering, but it’s one of those must-dos on the European circuit, like the Mona Lisa or the Parthenon. Truly a wonder.

Next up: The Tour d'Aï. To go to the start of these reports from Switzerland, click here .

Thursday, September 27, 2007

The Top of Europe. Sort of.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:58 AM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, September 25, 2007

Banff Photo Contest Winners

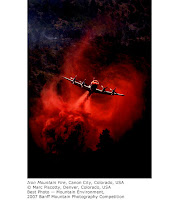

Winners of the 2007 Banff Mountain Photography Competition have been announced—17 prizes from more than 2,100 entries. You can see all the winners here. Marc Adamus of Oregon took the grand prize for a windy winter image, but I can't stop looking at the winner in the "Best Photo–Mountain Environment" category: Marc Piscotty's "Iron Mountain Fire," shot in 2002 near Canon City, Colorado. This striking image of a slurry bomber looks like a computer composite or poster from a science fiction movie, but it's the real thing.

Winners of the 2007 Banff Mountain Photography Competition have been announced—17 prizes from more than 2,100 entries. You can see all the winners here. Marc Adamus of Oregon took the grand prize for a windy winter image, but I can't stop looking at the winner in the "Best Photo–Mountain Environment" category: Marc Piscotty's "Iron Mountain Fire," shot in 2002 near Canon City, Colorado. This striking image of a slurry bomber looks like a computer composite or poster from a science fiction movie, but it's the real thing.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

10:19 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Monday, September 24, 2007

The Eiger Indirect

During the last day of our media tour in Grindelwald, we saw the Eiger from all angles: from the bottom, from the side, from the inside. Our trip had been organized around the past lives of John Harlin III, star of the new IMAX film The Alps and author of The Eiger Obsession: Facing the Mountain that Killed my Father. John’s father was John Harlin II, who made the first American ascent of the Eiger’s nordwand in 1962 and then died during a famed attempt on the Eiger Direct, now known as the Harlin Direct, four years later. In September 2005, the younger Harlin returned to Grindelwald to climb the Eiger north face—an event captured in the film.

Our Eiger adventure began by riding the yellow cog railway to Alpiglen, nearly 2,000 feet above Grindelwald. This is where Harlin II, Chris Bonington, and other Eiger aspirants too impecunious for hotel living would camp between attempts. From here, we switchbacked up the Eiger Trail past farmers’ gray wooden huts and huge, black, bearded goats with white bellies. This would be terrific hike below any mountain, with sterling views of Grindelwald and

the surrounding peaks, but the Eiger Trail is unique because of its close approach to such a famous landmark in climbing history. Walking here, it’s easy to imagine the Eiger pioneers hearing cowbells and the klaxon from the Grindelwald post bus from high on the wall. One envisions them freezing on the black face and longing for the green pastures below.

Along the path, Harlin stopped repeatedly to point out landmarks: the White Spider, Death Bivouac, the Hinterstoisser Traverse, the windowed viewing gallery from the Jungfraujoch train that we planned to ride that afternoon. Beneath the face, Harlin traced the direct route that his father had planned and led until he fell—young John stressed the “perfection of the line,” showing us how his father's route, which appears to wander a bit in the classic view from Kleine Scheidegg, actually creates a true direttissima.

My perspective was still off: As it did from town and from across the valley, the Eiger still appeared smaller than I’d expected; from this vantage, grossly foreshortened, it was hard to make out the famous features of the 1938 line until John painstakingly located them for us. It wasn’t until the end of the day, at Kleine Scheidegg, that the wall’s majesty and verticality were finally revealed to me.

Near the end of the walk, we crossed a broad scree slope, practically within rock-fall range of the face. A few people had left the main trail and hopped over talus several hundred yards to the actual foot; a few had even scrambled up the low-angle rock at the base, no doubt so they could say, “I climbed (sotto voce: 'on') the Eiger.”Just before reaching the end of the trail at the Eigergletscher stop on the Jungfraujoch rail line, we passed a steep band of limestone roughly 100 feet high, with a few icicles hanging from it. “Welcome to the Little Eiger,” John said. This was the stage set for re-enactments of certain of the most dramatic climbing scenes in the IMAX film. Although everything depicted in the film really happened, some of its was restaged here for the huge IMAX camera, during the spring after John’s climb.

Beside the train station was a smooth rock etched with the words “Den Eiger Kümmerts Nicht.” All along the path, we’d seen similar rocks with inscriptions in Swiss German; our guide explained that these told the epic tale of Swiss guiding history, filled with bureaucracy and infighting. The whole saga ends with this simple yet profound line: “The Eiger Doesn't Care.” Truer words were never carved in stone.

Next up: The top of Europe. Sort of. To go to the first of these stories from Switzerland, click here.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

3:20 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Thursday, September 20, 2007

Melting Mountains

Mountaineering in the Alps enjoyed its golden age, when most of the major summits first were climbed, during the 19th century. Ironically, the mid-19th century also marked the end of Europe’s Little Ice Age, during which Alpine glaciers reached their maximum length and depth in historical times. In other words, the glaciers on which the craft of mountaineering was born and nurtured have been retreating ever since climbers first kicked steps up them. And during the last few decades, the melt-off has accelerated dramatically. During our second day in Grindelwald, our group planned a short hike between the upper and lower Grindelwald glaciers. A few hundred yards from the road where we were dropped off, we stood at a bridge across a milky glacial stream, just below a cliff that rose nearly vertically for several hundred feet. A wooden catwalk snaked up the cliff to a café on top. The Upper Grindelwald Glacier was barely visible far behind the cliff, but our guide, Yeti (aka Beat Hutmacher), told us that just 20 years ago the place where we were standing would have been buried under grinding glacial ice. This is where old-time Grindelwald entrepreneurs used to cut ice blocks to ship in sawdust to the cities of France and Belgium. Less than a generation ago, Yeti taught ice climbing to beginners right here, where no ice can be seen today.

We switchbacked up a trail through the woods, and then Yeti led us about 50 feet down a side path to a small platform in the wet earth. “Right here there was an ice cave you could climb into.” A few minutes farther up the trail we reached a café with a broad deck. Yeti introduced us to the proprietor, Peter Bohren, the third generation of Bohrens to run this restaurant,

which was built on one of the lateral moraines from the now-vanished Upper Grindelwald Glacier. He showed us a photograph from the 1970s of patrons on the deck, enjoying a view of the churning ice nearby. “How’s business, now that the ice is gone?” I asked him. “Not so good,” he said.

We hiked along a bench above Grindelwald’s gorgeous emerald valley, and then, turning to the south, climbed steeply above the outlet from the Lower Grindelwald Glacier. The broad, icy north face of the Fiescherhorn rose above us, fluted like a peak in the Cordillera Blanca of Peru. Pale-blue seracs and white fields of snow gleamed in the sun. But the seeming abundance of glacial ice is an illusion. As we admired the view and ate a lunch of Käseschnitte (cheese on bread) at the Bäregg restaurant, we were surprised to learn that this hut was only two years old. The previous restaurant had slid into the abyss nearby as the glacier beside it retreated, loosening the rocks and earth under the restaurant’s foundation.

Walking down the trail again, Yeti stopped above a narrowing in the deep gorge and pointed to an enormous block of limestone that had detached from the opposite wall and slid forward into the canyon, leaving a broad gap between it and the cliff behind. This was the remnant from the famous “collapse” of the east face of the Eiger in the summer of 2006, when hysterical news reports declared that the Eiger was falling down as a result of global warming. News helicopters and thousands of hikers staged a vigil after a widening crack in the wall appeared, waiting for the big collapse. When it came, a cloud of dust briefly covered Grindelwald below, but the feared damming of the glacial stream in the canyon (and possible subsequent flooding) did not occur. The Eiger still stands, and, especially in light of the frenzied news reports, the “collapse” of the east face seems monumentally anticlimactic, though it did create a lovely pinnacle in the gorge, clearly visible from our hotel.

Still, I came away from the day’s hike with a new appreciation for the speed and extent of the changes under way in the Alps. Many experts in Switzerland predict that glaciers below 4,000 meters in elevation will be almost entirely gone by the end of this century—perhaps much sooner. Lives and businesses are being altered by the glacial retreat, but mostly there is a sense of sadness and loss: The snowy, ice-draped Alps we have known all of our lives, and through the stories, photos, and 19th century illustrations of the pioneers, are rapidly being denuded of their icy mantle. The peaks will still stand when our grandchildren visit, but they won’t look the same. The climbing difficulties will all be on rock (much of it loose, newly exposed, and unpleasant) instead of ice. The stories written on and about these mountains will be different from the ones we’ve known in the past. Will they measure up?

This summer, my wife urged me to visit Africa, a destination I’d planned to save for the less vigorous adventures of my old age. She argued that we needed to see the rare animals before they disappear forever. I feel the same way about the Alps, and the other alpine environments around the world—I want to visit them right now. Future generations undoubtedly will love the Alps in a new way, but to see these mountains and to climb among them the way we have since mountaineering was born—to witness and share the collective experience of more than 200 years of mountaineers—you have to go now. You simply can’t wait.

Next up: The Eiger Indirect. Click here to go to the first of these dispatches from the Swiss Alps.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

10:36 AM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, September 19, 2007

And Now For Something Completely Different

No time today for a new report from Switzerland, so here's one more from the Monty Python archives. Last month it was the fatal attempt on the North Face of Uxbridge Road. Now...the International Hairdressers Expedition to Mt. Everest.

Back to Switzerland tomorrow....

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

5:12 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, September 18, 2007

Power Hiking

My visit to Grindelwald this month coincided with the Jungfrau Marathon. This brutal race has more than 6,000 feet of elevation gain, yet roughly 4,000 runners attempt it each year. (In a coup, Colorado runner Galen Burrell finished fifth this time.) The local minder for our media tour, Martin Strahm, frequently runs from his office in Grindelwald to a hut about 1,800 feet higher, and he claimed he wasn’t in good enough shape for the Jungfrau Marathon. The 200-plus kilometers of trails around Grindelwald are packed with hikers of all shapes and sizes, and I haven’t seen as many big mountain boots on the feet of downtown pedestrians since Boulder in the 1970s. So...these people are fit, and there's no doubt they could hike (or bike or run or ski) up the local trails as often and as fast as they wanted.

But here’s the thing: With convenient lift access to the high peaks and meadows around Grindelwald (and throughout much of the Alps), it’s not surprising that many people don’t bother to hike both ways, up and down. Personally, I’m all for power hiking, as in the power assist of a speedy gondola. It's easier on the lungs going up and on the knees coming down. In the afternoon of Day 1 of our media tour of Switzerland, we rode gondolas in several stages to the First (pronounced "Feerst") ski station north of Grindelwald, rising from around 3,500 feet in the center of town to over 7,000 feet, high above the trees, in a matter of minutes. A cold rain had fallen in town the previous day, and a few inches of new snow lay on the ground at the top. But, though the temps were still brisk, the sun shone brilliantly.

In the afternoon of Day 1 of our media tour of Switzerland, we rode gondolas in several stages to the First (pronounced "Feerst") ski station north of Grindelwald, rising from around 3,500 feet in the center of town to over 7,000 feet, high above the trees, in a matter of minutes. A cold rain had fallen in town the previous day, and a few inches of new snow lay on the ground at the top. But, though the temps were still brisk, the sun shone brilliantly. Our small group followed a gravel road for about 40 minutes to the Bachalpsee, a tarn nestled among high peaks. We were in the middle of a ski resort, but it didn’t feel like it: The lifts were far in the distance, and the only signs we saw pointed out hiking routes. In the winter, the road we were following is packed with Sno-cats, and winter hiking is a popular way to explore the Swiss mountains—no skis or snowshoes necessary. This road also leads to the start of a remarkable 15-kilometer, 1,500-vertical-meter toboggan run that is packed out of the snow each year—a must-do someday.

Our small group followed a gravel road for about 40 minutes to the Bachalpsee, a tarn nestled among high peaks. We were in the middle of a ski resort, but it didn’t feel like it: The lifts were far in the distance, and the only signs we saw pointed out hiking routes. In the winter, the road we were following is packed with Sno-cats, and winter hiking is a popular way to explore the Swiss mountains—no skis or snowshoes necessary. This road also leads to the start of a remarkable 15-kilometer, 1,500-vertical-meter toboggan run that is packed out of the snow each year—a must-do someday.

Now, the full scope of Grindelwald’s peaks was revealed—one of the great mountain walls of Europe. The Wetterhorn, Schreckhorn, Lauteraarhorn, Finsteraarhorn, Fiescherhorn, the Eiger, the Mönch, and Jungfrau. Ironically, among all these giants, the Eiger doesn’t top 4,000 meters, but its presence is palpable. From the valley floor in Grindelwald, the Eiger rises more than 9,000 vertical feet to the 13,025-foot summit—nearly 6,000 feet of that in the Nordwand itself. From Grindelwald and the First side of the valley, the Nordwand doesn’t appear quite as steep as it does in the classic view from Kleine Scheidegg, and I couldn’t begin to grasp the scale—at first I was underwhelmed. I had to force myself to imagine two El Capitans stacked atop each other on that steep wall.  In late afternoon, we hiked down a steep valley to the Waldspitz restaurant and hut, perched on a forested ridge at about 6,250 feet, still 3,000 feet above town. We drank a beer on the sunny deck and then, as the evening chill descended, we moved inside, where there were tables for about 30. During dinner we had to keep running out to the deck as alpenglow fired up the great peaks of the Bernese Oberland. Martin said

In late afternoon, we hiked down a steep valley to the Waldspitz restaurant and hut, perched on a forested ridge at about 6,250 feet, still 3,000 feet above town. We drank a beer on the sunny deck and then, as the evening chill descended, we moved inside, where there were tables for about 30. During dinner we had to keep running out to the deck as alpenglow fired up the great peaks of the Bernese Oberland. Martin said  Grindelwald residents often hike up for dinner and spend the night at the Waldspitz, or make it the midway stopover on the spectacular two-day hike from Schynige Platte to Grindelwald. But we were power hiking today, and long after dark a taxi driver appeared at the door. After stepping inside for a quick coffee, he ushered us into his van and drove our tipsy crew down the winding road to our hotel.

Grindelwald residents often hike up for dinner and spend the night at the Waldspitz, or make it the midway stopover on the spectacular two-day hike from Schynige Platte to Grindelwald. But we were power hiking today, and long after dark a taxi driver appeared at the door. After stepping inside for a quick coffee, he ushered us into his van and drove our tipsy crew down the winding road to our hotel.

Next up: Melting Mountains. Read the first Swiss report here.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:59 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Monday, September 17, 2007

Destination: Switzerland

Although I’ve been climbing for three decades, I had never climbed in Switzerland, where the mountaineering tradition is older than just about anyplace else. So, when an invitation to join a media tour in the Swiss Alps in early September suddenly appeared, I leapt at it. I hoped that a gambol around the Bernese and Vaudoise mountains would improve my sense of Alpine geography, which is woefully inadequate and confused. Like most non-European climbers, the Alpine peaks I could easily recognize were limited to the Matterhorn, Mont Blanc, the Eiger, and perhaps a few other giants. For example, I’ll bet most American climbers could not name the lovely pyramid in the photo above. Until this month, I wouldn’t have been able to either, but now I can: It’s the Schreckhorn , said to be one of the most difficult 4,000-meter peak in the Alps. And now it's on the long and seemingly ever-growing list of peaks I want to climb someday.

First stop on our tour was Grindelwald, the lovely green-pastured town at the base of the Eiger (and the Schreckhorn). Like most mountain resorts, Grindelwald has expanded its sport menu far beyond traditional skiing and mountaineering, and so our crew of five North American journalists was treated to a whirlwind of alternative “extreme” sport offerings. Our morning outing was led by Yeti, aka Beat Hutmacher, an affable bergführer (mountain guide) from Interlaken. I had to laugh as we roped up as a team of eight and marched into a gently sloped woodland to approach our first adventure.

First stop on our tour was Grindelwald, the lovely green-pastured town at the base of the Eiger (and the Schreckhorn). Like most mountain resorts, Grindelwald has expanded its sport menu far beyond traditional skiing and mountaineering, and so our crew of five North American journalists was treated to a whirlwind of alternative “extreme” sport offerings. Our morning outing was led by Yeti, aka Beat Hutmacher, an affable bergführer (mountain guide) from Interlaken. I had to laugh as we roped up as a team of eight and marched into a gently sloped woodland to approach our first adventure.  But soon we were descending along exposed ledges, clipped into via ferrata cables, with a guide at either end to hold the rope.

But soon we were descending along exposed ledges, clipped into via ferrata cables, with a guide at either end to hold the rope. Our goal was the top of the Glacier Express, a steel-cable zip line that starts from a clifftop about 50 meters above the Lütschine River and swoops 350 meters (nearly a quarter-mile) to a platform at the far end. We would hit speeds of 40 kilometers per hour (about 25 mph) during this run, and it wasn’t at all clear how we would avoid smashing into the trees at the cable’s end. But as I flew toward the woods, screaming involuntarily, the answer was revealed: A guide stood ready to apply the brakes with a climbing rope snubbed around a belay stake in the ground. I coasted to a stop right on the wooden platform, breathless.

Having survived the zip line, we hiked back to the top of the Glacier Gorge, the tight-walled outlet for the Lower Grindelwald Glacier, for a bit of “rappelling.” In fact, the "Spider Highway" turned out to be a series of lowers rather than rappels. Like most climbers, I don’t much like rappelling, and I hate being lowered, in part because I once was dropped to the floor while lowering in a gym. And so I was almost as gripped as the non-climbing journos as we set up at the top of 250-foot-deep gorge. (I counted my blessings that we weren’t going for the bungy jump or pendulum swing into the narrow canyon—launching platforms protruded diving-board-like from the canyon rim.) The guides lowered us each in turn down the overhanging limestone cliff: around 30 meters to a platform bolted to the wall, and then a second lower of about 45 meters, through a hatch in the platform, to another wooden ledge just above the river.

We still had to cross the river to reach the trail on the far side, and the route was a tight-rope walk across a steel cable; we clipped into another cable overhead for safety, with a third cable for a much-needed armrest. Totally safe, but surprisingly difficult and exciting. The zip line, the canyon lower, the cable traverse—these are the sorts of pseudo-adventures that "real" climbers routinely scoff at. But once you try them, they're a blast.

With the extreme stunts out of the way, we sat down for a lunch of rösti—a sort of hash brown—to fuel up for more traditional Alpine fare in the afternoon: gondola-powered hiking.

I’ll be posting frequent reports from my Alpine sojourn over the next couple of weeks. Come back tomorrow for the next installment.

Posted by

Dougald MacDonald

at

7:50 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()